Any organization that collects and stores EU resident data is subject to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Examples of such organizations include Google, Facebook, and Amazon. The regulation places the obligation for responsible data handling with such organizations, and gives individuals a number of rights. All major geographies now have GDPR-like regulation or are in the process of passing one. GDPR-like regulation for India is called PDP (Personal Data Protection) Law.

Right to Forget

One of the key rights that individuals have under these regulations is a “Right to Forget”. It empowers individuals to request erasure of all non-essential data, as defined by the regulation, related to them across all databases and data sources throughout the organization. Organizations are required to implement the request, and give an explanation if they don’t. If they are proven to be in violation of the right, for example by sending an innocuous marketing email, the organization is in violation of the regulation, and may attract severe penalty.

The implementation of ‘Right to Forget’ is complicated due to the fact that it might require modification of data in place (especially for large datasets), cover all datasets (has to be exhaustive), and the fact that data has been deleted has to be demonstrable.

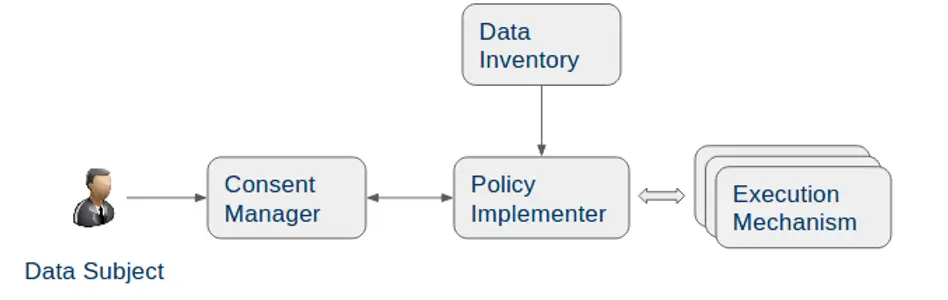

This requires a system and process for obtaining and tracking requests from the data subject or individual, and implementing them using a fit-for-purpose mechanism with appropriate audit trails.

Hard Delete and Soft Delete

There are two major approaches that an organization can use to implement the ‘Right to Forget:’ Hard Delete and Soft Delete, based on whether the underlying data is modified or not.

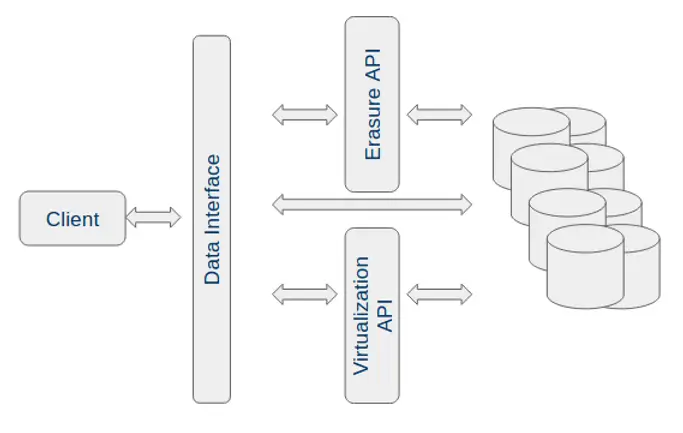

In all cases, the access to data is mediated through an API. We see three kinds of access paths:

-

Default – Standard interface to the backend as defined by the implementation such as ODBC.

-

Erasure API – API to receive the erasure requests from the consent management, implement them, and provide evidence for the same.

-

Virtualization API – API to proxy data requests, and erase records or parts of records as required without modification. The API should mimic the backend API such as ODBC.

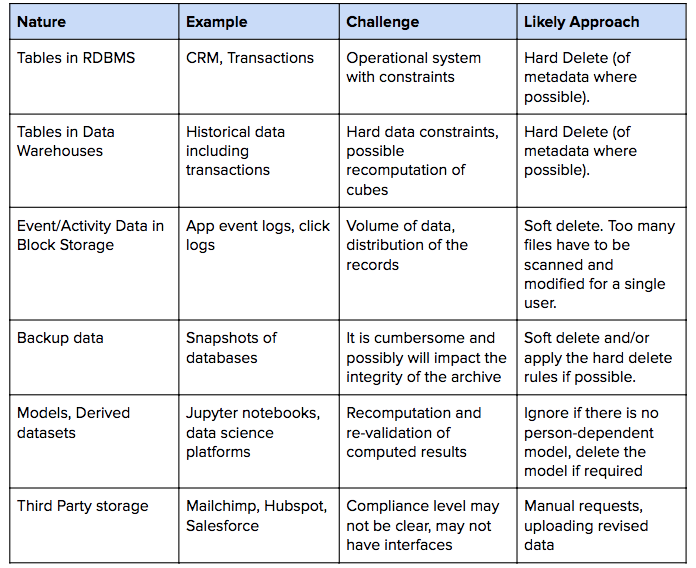

Hard deletes: As the name suggests, this approach would require the organization to delete the User’s data such that it can’t be reproduced once deleted. The copy of data at rest, whether in databases or files, is modified to eliminate the relevant records. Hard deletes can be further classified as metadata deletes or raw data deletes. In the case of the former, only the key lookup tables or metadata are deleted. This method is appropriate when the PII is completely factored out into a separate table, and the rest of the data is useless without the right metadata records.

Soft deletes: This approach does not modify the underlying data, but achieves the goal by introducing a data virtualization layer that sanitizes the data as it passes through.

Hard deletes are harder to implement, and may have potential side effects such as invalidating derived artifacts such as models or constraint violations. Soft deletes are easier to implement as a ‘patch’ over an existing system. We expect to see both mechanisms in organizations based on cost and complexity of the implementation. It is unclear what is legally acceptable, but demonstration of intent to comply is critical.

Common Sources of Data

Other Implementation Considerations

There are a few other considerations during implementation:

-

Auditability: The system must maintain audit logs of changes to the data made, when, and ideally with a link back to the consent manager. These audit trails will likely have to be provided to the regulatory body.

-

Catalog: A comprehensive catalog of the data is required to implement the various erasure mechanisms.

-

Reporting: It is not enough to provide audit logs of the changes, it is necessary to format the output in a way that is accessible and acceptable to the legal and administrative stakeholders internally and externally. It is worth standardizing and automating the reporting structure given the repeated nature of the activity.

References

A deep dive into the right to be forgotten

How fortune 100 companies implement CCPA right of erasure

Do check out Carver Agents’ RegWatch – our new AI solution for real-time contextual regulatory risk intelligence, built for risk and strategy executives. Think of it as agentized mid-market LexisNexis. Visit https://carveragents.ai/.